A takeaway from “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture.”

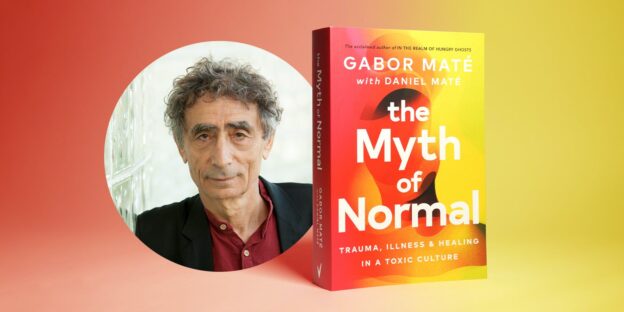

I’m close to finishing Dr Gabor Maté’s latest book — “The Myth of Normal”, which is a book I wished I had read instead of listened to. It’s the type of book you’d want to read while taking notes, pausing and thinking, and even going back through pages to re-read and understand certain passages better.

Dr Maté’s renowned success doesn’t require any reinforcement, especially now with the release of his new book, so the intention behind this apparently promotional article is actually to help people that haven’t had the chance to read the book yet, to access one of the most important, in my opinion, of course, takeaways of this book.

This is a self-inquiry exercise that Dr Maté proposes to take daily, weekly, or at any frequency you wish, as long as you commit to a schedule and do it at least once a week.

The purpose of the exercise is motivated by the fact that we’re not our personalities. According to Dr Maté, personality is an adaptation or, to some extreme extent, a coping style that doesn’t necessarily reflect who we are. Our personalities are shaped from the moment we’re born throughout our lives through our interactions with our caretakers, family, community, and society at large. So, the advice is not to mistake our personality for our identity.

The book’s leitmotiv revolves around healing, in the sense of reconnecting to what is essential and authentic about us; hence, this exercise consisting of the six questions designed by Dr Maté is meant to help us find our way toward our authentic selves.

Commitment is important to derive any meaningful results from it, but equally important, Maté encourages us to use compassionate curiosity to ask ourselves why in the event we happen to employ the lamest excuse in the world — Yes, I’d do it, but I don’t have the time. According to him, and I second that, we all have the time, yet not all of us we have a strong sense of intention for its use. I really loved this explanation, which is why I emphasise it here.

Whatever the reason may be, he urges us not to shame ourselves.

Prerequisites

- Have a strong sense of intention to commit to this exercise for some time.

- Find a quiet room, free of distraction

- Get a notebook and a pen. Handwriting will engage your mind more actively and profoundly, help you connect with yourself, and enable the tracing of your progress over time.

Question #1 — What am I not saying “no” to in my life’s important areas?

Dr Gabor Maté asks us to be current and stay specific. He explains further: “where did I, today or this week, sensed a no in me, but I stifled it or said a yes when a no would have been in order?”.

We should be looking for chronic patterns, not for mindful of heartfelt decisions to support others or care about them. Dr Maté gives the relatable example of parents caring for children during sickness or attending to a friend’s needs authentically. He kindly comforts us by saying that “we don’t stigmatize genuine caring”.

We must pay attention to “the unwilled selflessness engrained in our personalities — the one that takes a heavy toll” Dr Maté advises us for this part of this exercise and gives us several practical examples we could all relate to.

At work, it can be the additional task that overburdens us or the work we take over the weekend at the expense of our family time. It could be us saying “yes” to a co-worker who removes our focus from our tasks or the feedback we gave saying what we thought they wanted to hear, not what we would have needed to say.

In our personal lives, unwilled selflessness could have manifested when we accepted to go out with a friend when instead we needed rest or when we engaged in sex with our partners even though we weren’t exactly ready after a fight. Similarly, it could be us not taking the needed space and opting against asking our partners to mind the kids for a while or, finally or not sharing the load with our siblings when caretaking for our aging parents.

Dr Gabor Maté helps us further dig into this question by asking us a follow-up: “With whom and in what situations do I find it most difficult to say no?”.

And if we do, then do we do so reluctantly, apologetically, or with guilt? Do we beat ourselves after it?

The impact of not saying “no.”

This was already covered in his famous book “When the body says no”, but he reiterates here the main effects of not saying no on the physical, emotional and interpersonal layers.

- physical: insomnia, back pain, muscle spasms, dry mouth, frequent colds, abdominal pains, digestive problems, fatigue, headaches, skin rashes, loss of appetite or urge to overeat.

- emotional: sadness, alienation, anxiety, boredom, loss of pleasure, dulling sense of humour.

- interpersonal: resentment towards the people or situations where the authentic answer was stifled (ironic).

Question #2 — What do I miss out on due to my inability to assert myself?

He doesn’t cover this question extensively as it is rather self-explanatory but gives several guiding examples such as fun, joy, spontaneity, respect, libido, opportunities for growth and adventure.

Question #3 What bodily symptoms have I been overlooking?

This question brings us back to the impact of not saying no, on our bodies. Dr Maté invites us to run an inventory of our bodies daily or weekly. He explains that this is an essential backup measure for those of us that don’t even realize how much they are suppressing. We should aim to regularly survey our symptoms, such as fatigue or persistent back pain, and ask ourselves what unsaid no these might be signalling.

However, he correctly points out that to spot them, we need to be able to pause long enough to observe them and ask if they become chronic many of us learned to ignore these signals.

For those that feed on the adrenaline of the stress, it may prevent our bodies from crashing.

Question #4 — What is the hidden story behind my inability to say no?

For this question, Dr Gabor Maté, invites us to reflect on the narrative, explanation, justification, or rationalization that makes these habits sound normal for us, and he further explains that most often, they sprout from limiting core beliefs about ourselves.

We should strive to identify the underlying narrative or the story behind the story. For example, why do we resign ourselves, saying that considering how X is behaving is easier not to say no, than go through the hassle?

Dr Gabor Maté admits that it may be difficult to find the story, so he helps us with a guiding follow-up question: “What must I believe about myself to deny my own needs this way?”

But why do people not say no? This can stem from beliefs like saying “no” means we can’t handle something, it’s a sign of weakness, and we must be strong.

We also tell ourselves we must be good to deserve to be loved because, consequently, if we say no, we’re not lovable. Also, another narrative is that we are responsible for other people’s feelings and experiences, so we mustn’t disappoint anyone. We are not worthy unless we’re doing something useful. And, if people knew how we actually felt, they wouldn’t like us. We would let down x, y, and z. Because it’s selfish to say no.

Dr Maté candidly explains the implied double standard in this narrative because we wouldn’t feel the same if our x, y, and z would say no to us if that’s what would have felt true to them. Yet, we hold ourselves to impossible standards.

He continues reflecting on this idea with other relatable examples. We wouldn’t charge our neighbours with selfishness if they said no to us, as we wouldn’t tell our children worthless unless they make themselves useful.

Question #5 — Where did I learn these stories?

Dr Gabor Maté brings us back to our roots with this question. He explains that no one is born with a sense of worthlessness. Sadly, interaction with our caregivers makes us believe in ourselves in a certain way. As children, we take it personally if our caregivers treat us badly due to their own trauma and equally if they are stressed or distressed for whatever reason unrelated to us.

According to Dr Gabor Maté, our caregivers make us question our value.

He invites us with this question to look at the past in a manner such that we don’t dwell on it but learn from it and let it go. Once we understand how our suffering came to be, Buddha said, we’re already on the path of healing.

In short, this question calls for a frank look at our childhood experiences, not as we would have liked them to be, but as they were.

Question #6 — Where have I ignored the yes that wanted to be said?

Finally, Dr Gabor Maté asks us to treat the withheld “yes” with the same criticality as the stifling “no” because both can make us ill. He invites us to reflect on the occasions when we sacrificed the “yes” in the name of duty or because of sheer fear.

We need to ask ourselves, Dr Gabor Maté continues, what desire to play or explore we have ignored or what joys we have denied ourselves?

Committing to practising this exercise for a la long may prove life-changing for many of us. It can help us identify patterns in our lives that require a swift change, and it can literally save our bodies from crashing.

Read the book. It’s worth it.

Source:https://medium.com